Lough Gill is a freshwater lake near Sligo in west Ireland. The 5-mile-long lake, where people walk the nature trails through the surrounding woodlands, watch birds, and kayak on the water, is associated with a famous poem by the great Irish poet William Butler Yeats. The lake is not the focus of the poem. Instead, the poet draws our attention to a little island, the one you see here, whose name is Innisfree. Yeats wrote meditatively and symbolically about that island in a famous poem, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.”

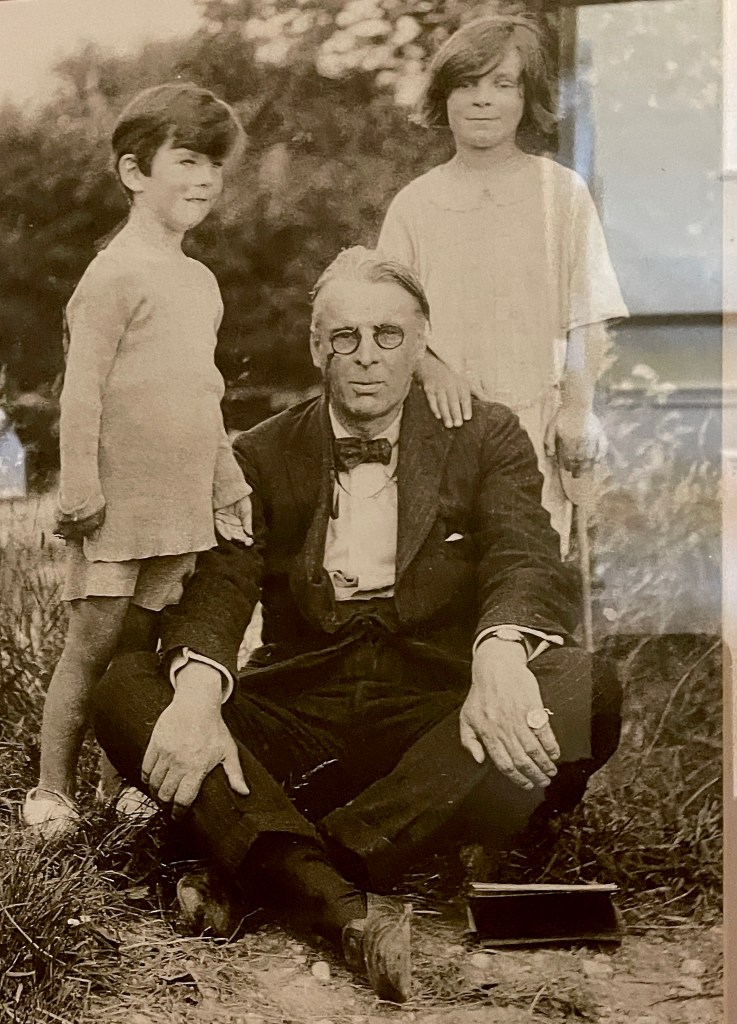

Yeats (1865-1939), who is buried in Drumcliff, 5 miles north of the town of Sligo, would spend summers in this region when he was a child and youth. If you travel through this country, as we did early this month, you’ll see a number of tributes to him, like the Yeats Country Hotel at Rosses Point, a little bit of land jutting into the sea where he and his family would vacation; a visually arresting statue of him (erected in 1989) in Sligo, a B&B named after him, and so on.

“The Lake Isle of Innisfree” was written in 1888 and first published in 1890.

<<<<<< >>>>>>

THE LAKE ISLE OF INNISFREE

by William Butler Yeats

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

<<<<<< >>>>>>

Yeats spoke about his inspiration for the poem in a moving and, for anyone interested in the creative process, fascinating way. The passage is almost as famous as the poem: “I had still the ambition,” he wrote, “formed in Sligo in my teens, of living in imitation of [Henry David] Thoreau on Innisfree, a little island in Lough Gill, and when walking through Fleet Street [in London] very homesick I heard a little tinkle of water and saw a fountain in a shop-window which balanced a little ball upon its jet, and began to remember lake water. From the sudden remembrance came my poem ‘Innisfree,’ my first lyric with anything in its rhythm of my own music.”

I first read Yeats’s poem in a course on modern poetry that I took in my final semester as an undergraduate a long time ago in The Bronx. The course was one of my most important learning experiences. I still have and still occasionally read my copy of the course text, Modern American and Modern British Poetry, an exhaustive anthology compiled by Louis Untermeyer and originally published in 1922 with later editions, including a revised, shorter edition published in 1955, which was the text we read. Until we began that course in mid-January 1969, I had never read anything by Yeats, T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, W.H. Auden, Wallace Stevens, Dylan Thomas, and other poets.

“The Lake Isle of Innisfree” was the first poem we read. After reading the poem aloud, our instructor, a classy Southerner with a tremendous passion for poetry and Shakespeare, opened the talk by placing Yeats’s poem into a broad cultural and political moment, the fin de siècle (“end of the century”). The term is often applied to the end of the 19th century and is taken to mean that Western culture (especially in France) was going through a period of lassitude, decadence, and decline. The professor pointed to the mood of the poem and in particular the first line: The speaker has been sitting or lying down and perhaps doing nothing more than thinking or dreaming, but nothing seriously worth mentioning. The poem doesn’t really start, doesn’t demand our attention, until he decides to get up and build his little Thoreauvian cabin, a refuge from the world, a place for solitude and contemplation but not for action in the social sense. He’ll be alone with the bees and the softly lapping water. He won’t engage with human institutions or his fellows.

How many people today feel exactly the same way as the poem’s speaker, who decides that the “bee-loud glade” and the song of the crickets and the “dropping slow” peace are all preferable to the ceaseless activity and madness of the cities and suburbs that we’re all trapped in? Many Alaskans, I’m sure, know exactly what I’m talking about.

By the way, I urge readers to listen to Yeats recite his own poem. I was much surprised when I first heard it. I never expected that Yeats’s “music” was so incantatory, although actually seeing his little island and knowing he was thinking about that place while walking around London makes me understand his poem more than I ever did.